What is Visual Literacy?

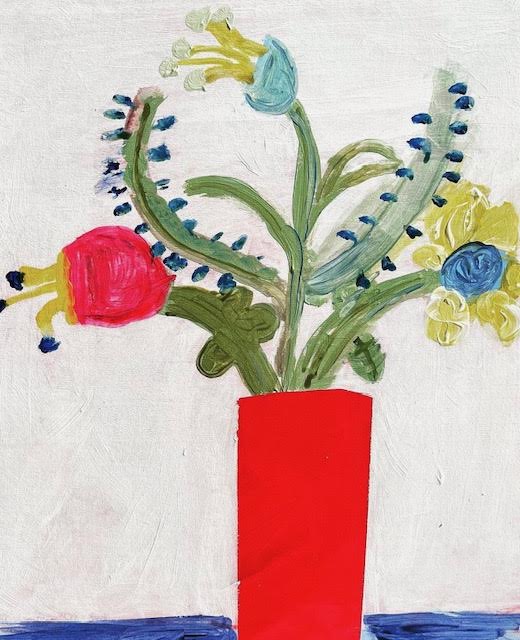

Visual literacy is the ability to understand and interpret the images and visuals we see around us every day. Just like learning to read words, visual literacy is all about learning how to “read” pictures, symbols, and even videos. Whether it’s a painting, a cartoon, or a road sign, being visually literate means you can figure out what those images are trying to tell you. It helps us notice details like color, shape, and movement to understand the bigger message that’s being shared through art or design.

Why is Visual Literacy Important?

Visual literacy is important because we live in a world full of images—on screens, in books, and even on the streets. By learning how to understand these visuals, kids can better navigate their environment and communicate more effectively. It also helps with critical thinking, teaching us how to analyze what we see and decide what it means. Being visually literate makes it easier to appreciate art, understand media, and even create your own visuals that tell a story or share an idea. Plus, it’s a fun and creative way to develop important skills for school and life!

How to decode art: UK schools embark on ‘visual literacy’ week

As the government aims to put the arts at the heart of the curriculum, an Art UK project is teaching children how to ‘cope with today’s image-saturated world’

The Art Newspaper 2 October 2024

In her address to the Labour Party conference, the UK culture secretary Lisa Nandy recently stressed that “a complete education is a creative education”

All primary-school aged children in the UK will be taught how to “read” art during a special visual literacy week running until 6 October. According to Art UK, the charity behind the initiative, the scheme will enable children aged 7-11 to “cope with today’s image-saturated world”.

Visual Literacy Week is comprised of a series of articles, webinars and an online “school trip”, and will culminate in a symposium at Yorkshire Sculpture Park on 5 October.

Schools can also sign up to a virtual “art adventure” taking place today (2 October), through which artist Sarah Graham explores works on show at The New Art Gallery Walsall and Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow. The project includes discussion prompts and activities for classes.

Crucially, teachers can undertake training sessions in how to use free resources from The Superpower of Looking, which uses works of art to teach primary school pupils how to decode meaning in images, from emojis to Old Master pieces.

For instance, teachers’ notes for David Hockney’s work My Parents (1977) housed at the National Gallery in London, include “nudge questions”. These include “What are your first impressions of David Hockney’s parents? Do you think this painting looks realistic? Why/why not? What sounds and smells do you think you would experience if you entered the painting?”.

The Superpower of Looking is funded by the Freelands Foundation and was co-devised by Alison Cole, the director of the arts and creative industries policy unit at the Fabian Society and former editor of The Art Newspaper. A recent report from the Fabian Society, Arts for Us All, advocated the teaching of visual literacy skills.

Andy Ellis, the chief executive of Art UK, says that the charity’s aim is to support every school child to be “visually literate” by 2030. According to the organisation’s website, The Superpower of Looking “enables teachers to deliver many aspects of the art and design curriculum, as well as providing exciting new interdisciplinary approaches to learning”.

In her address to the Labour Party conference 24 September, the UK culture secretary Lisa Nandy stressed that “a complete education is a creative education. And that is why Bridget [Phillipson, Secretary of State for Education, Minister for Women & Equalities] and I have kickstarted a review of the curriculum to put arts, sports and music back at the heart of our schools and communities where it belongs.” The timeline of this review is unclear.